Ilya Sprindzhuk

Ilya is a visual artist, and author of paintings and installations, actionism and new media activities. He was born in Minsk, Belarus. Since 2021 has lived and worked in Warsaw.

Ilya's works take the form of objects-installations that invade space. He often refers to themes of presence, identity, insecurity, and the right to be heard.

Ilya's works take the form of objects-installations that invade space. He often refers to themes of presence, identity, insecurity, and the right to be heard.

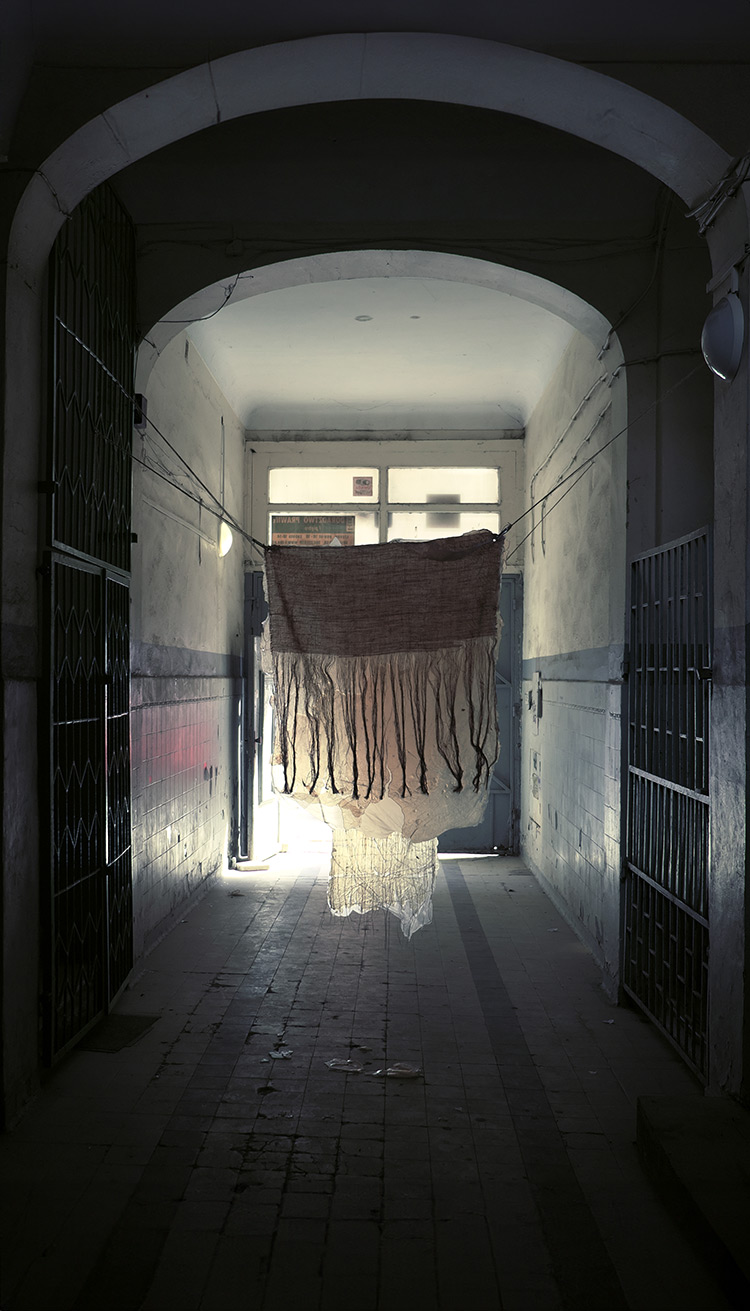

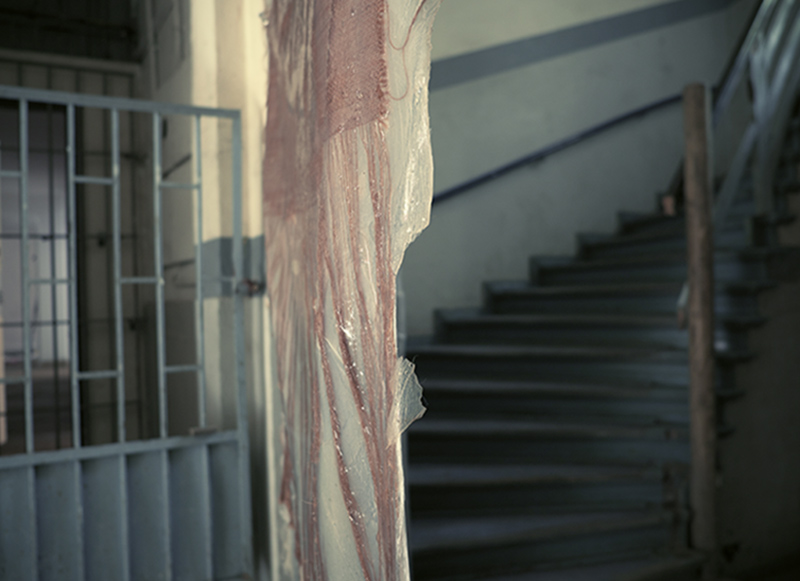

A site-specific installation featuring semi-transparent bioplastic canvases symbolising boundaries, allowing glimpses beyond. By combining natural and unnatural characteristics of materials and artistic methods of hanging and stretching the canvases in the space, the artwork highlights the artificiality of separation, questioning its validity. The installation oscillates between visibility and non-visibility. The environment in which the installation is placed can influence its properties and, under certain uncontrolled circumstances, affect its decomposition.

Recently, I have been experimenting with various materials, gradually integrating them into my practice — their contextual content, as well as new possibilities (and impossibilities) intrigue me. Turning specifically to new materials is closely related to my active practice in painting/objects, strongly manifested in the Procesual Painting series. While I take the experience of this series as some basis for a new installation, its context will only be a source for developing new themes. The installation will centre around notions of border, boundary (borderline?), and the relation of space/time.

Recently, I have been experimenting with various materials, gradually integrating them into my practice — their contextual content, as well as new possibilities (and impossibilities) intrigue me. Turning specifically to new materials is closely related to my active practice in painting/objects, strongly manifested in the Procesual Painting series. While I take the experience of this series as some basis for a new installation, its context will only be a source for developing new themes. The installation will centre around notions of border, boundary (borderline?), and the relation of space/time.

Borderland / Borderless

Combining these two aspects (the Processual Painting series and my understanding of boundary issues), I have developed an installation that expresses these themes symbolically. The installation is a series of bioplastic canvases stretched on cables that separate space and create boundaries. "Natural" properties of bioplastic — its translucency and texture — allow the viewer to see the blurred image behind the canvas, thus accessing the space "beyond the border". Canvases restrict the viewer's movement, forcing them to slow down as they move through the space. Eventually, there is a possibility that the bioplastic will begin to decompose and disintegrate into nothingness. With this gesture, I want to raise the issue of the artificiality of boundaries and the problematic of any artificial separation.

He is interested in the subject of power and its impact on the current social framework. As a representative of a specific Belarusian culture and environment, he does not try to limit himself to telling only about it — it is important for Ilya to explore what can happen next and how it can be useful for world culture. His work became a constant struggle with universality but, at the same time, a search for it. In addition to art, he's working as a graphic designer, creating visual identities for cultural events, exhibitions and projects.

Ilya studied at the Minsk State Lyceum of Fine Arts, specialising in graphic design with an emphasis on academic drawing and painting, periodically participating in plein-air workshops in Poland. He entered the Belarusian State Academy of Arts, majoring in furniture design, but did not graduate and was expelled. After the start of the political crisis in Belarus in 2020, Ilya moved to Odessa and, in 2021, to Poland as a political refugee, fearing persecution by the Belarusian regime. In Warsaw, he began his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, majoring in New Media Art. Ilya's work encompasses a wide range of media, his works take various forms, including paintings, actions, installations and sculptures. Ilya works in the studio of the Prześwit Foundation in Warsaw's Old Town.

Ilya studied at the Minsk State Lyceum of Fine Arts, specialising in graphic design with an emphasis on academic drawing and painting, periodically participating in plein-air workshops in Poland. He entered the Belarusian State Academy of Arts, majoring in furniture design, but did not graduate and was expelled. After the start of the political crisis in Belarus in 2020, Ilya moved to Odessa and, in 2021, to Poland as a political refugee, fearing persecution by the Belarusian regime. In Warsaw, he began his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, majoring in New Media Art. Ilya's work encompasses a wide range of media, his works take various forms, including paintings, actions, installations and sculptures. Ilya works in the studio of the Prześwit Foundation in Warsaw's Old Town.

One of the additional motivations was the stories in the emigrant environment, which I often witness. A colleague who emigrated from Belarus to Poland was confronted with the death of her grandmother in Belarus. For a very long time, everything that happened in a country close to her was not real, inaccessible — as well as the emotions she did not feel in connection with the tragedy. For her, the story had not yet happened: the last time she was home was three years ago, and the image of home remained a mirage from three years ago. Unable to return to Belarus because of the threatened persecution and danger from the ruling regime, she faced a hopeless situation. In this case, the border was not simply a barrier between one state and another — the relation of territory to territory — but rather a problem of time and space. The real border was the inability to be somewhere mentally, to live the tragedy fully, to let it into her life. This state is characteristic of many migrants who have left the territories with which their lives are closely connected. The border is nevertheless an artificial construction, woven in hearts and minds but restricting the body.